Breakfast in Havana

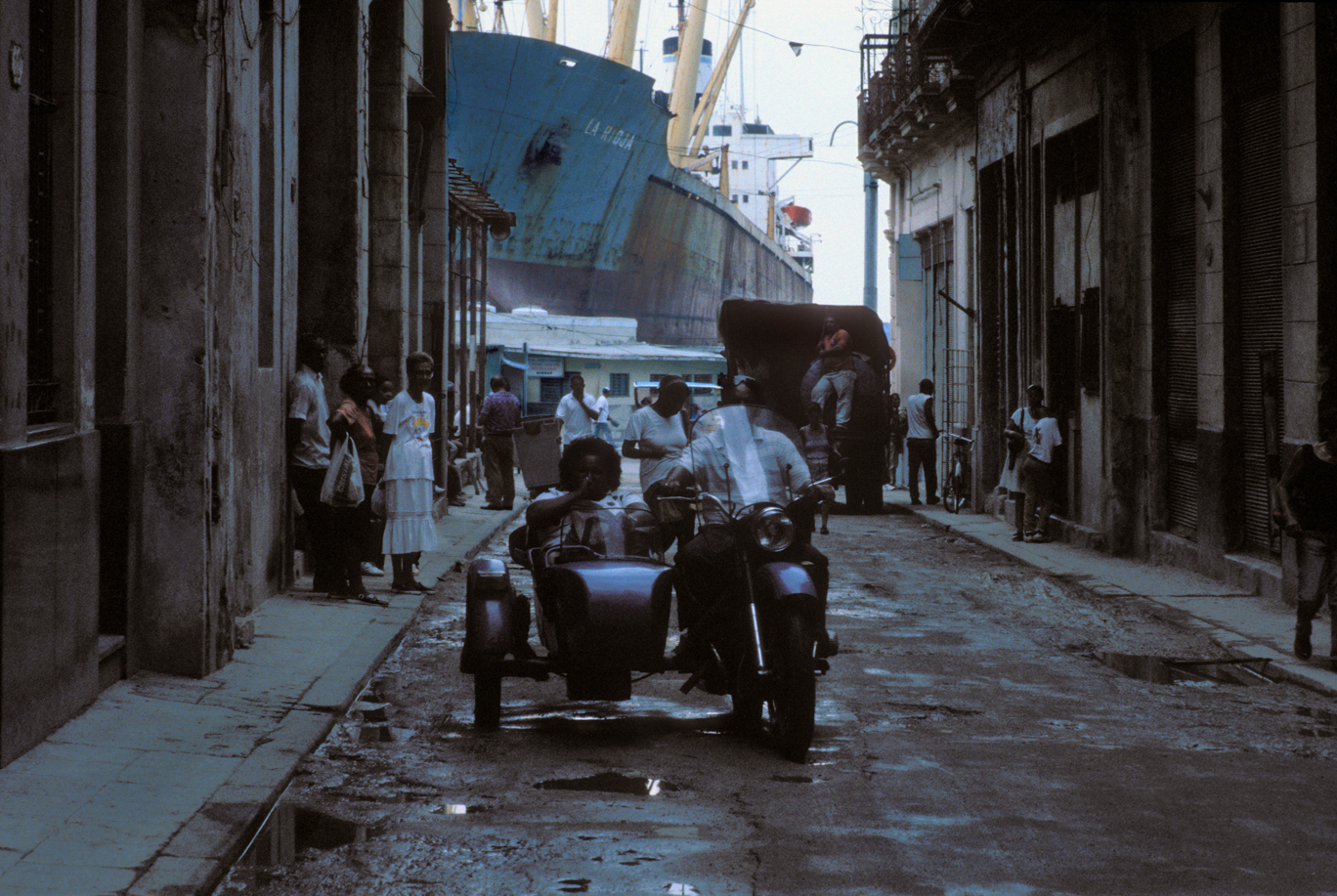

On our first visit, Havana greeted us with her impossible August heat and gorgeous balmy nights. Everywhere, young men and women drank rum, sang songs and flirted under a canopy of chestnut trees. As we walked through the unlit boulevards of the Old City, it felt like pure romantic Latin American heaven. Strangely, it reminded me of some place I’d been before. Only as we approached the port and saw the lights of anchored ships, it dawned on me that the place was Odessa – Ukrainian city on the Black Sea, where I’ve spent many summers of my childhood. The sound of breaking waves, the humidity, Spanish and French architecture, dusty boulevards lined with chestnut trees – well, Havana was Odessa, in every sense, but multiplied by a hundred.

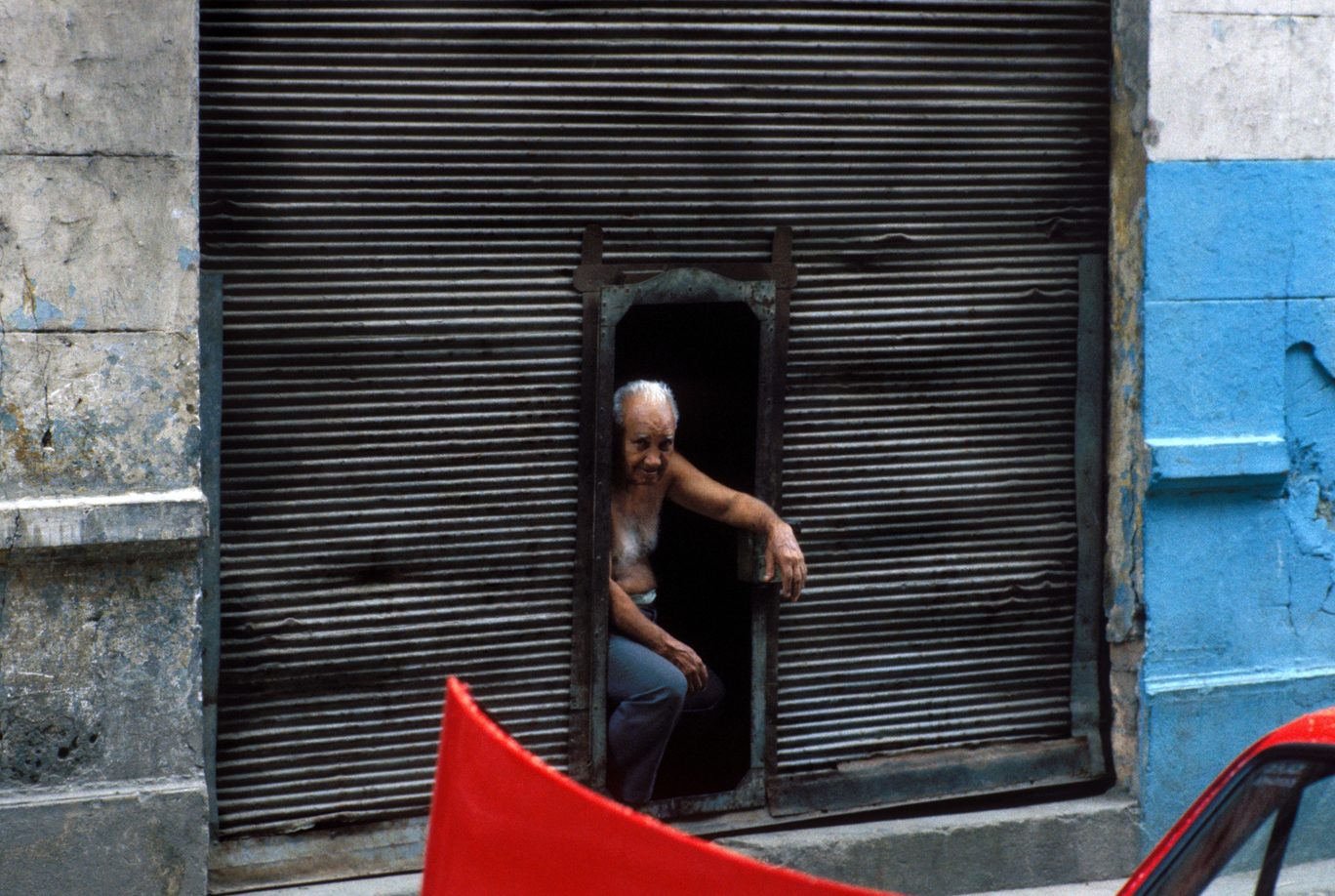

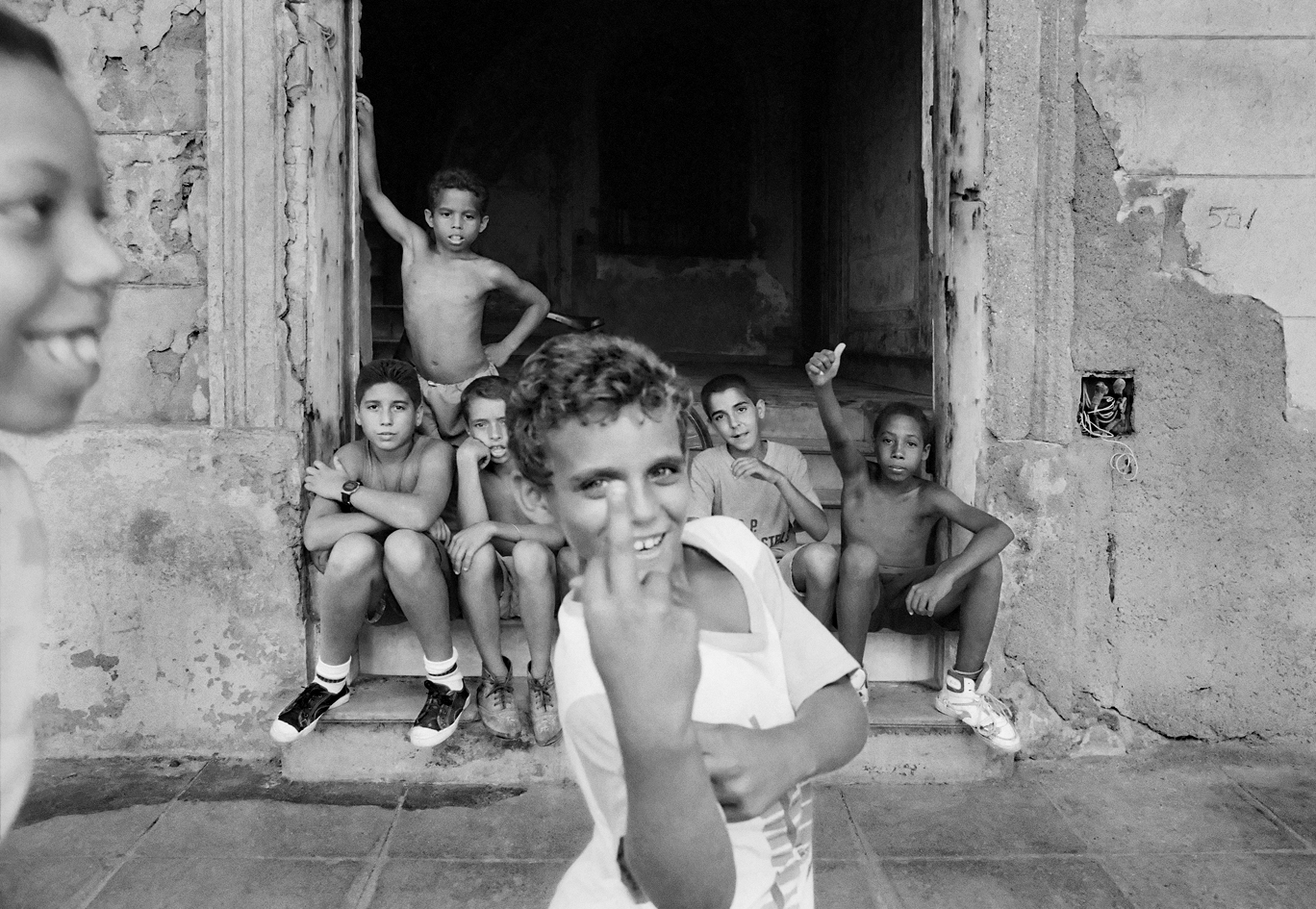

The pitch-dark streets of Cuba’s capital were not at all menacing, but friendly and inviting, touched with a mysterious sensuality. The “amor” was permeating the thick tropical air, filling the colonial arches of crumbling Havana Vieja. “Soy un chico bueno, signor!” – came a high-pitched voice from a bench nearby. There were many “good girls” and “good boys” out on the street, selling their friendly services, in hope of covering their monthly rent with a single night’s dirty work.

Next morning, as the sun rose over Vedado, the neighborhood where we stayed, another view came to light, also strangely familiar to my eyes. It was a regular workday and habañeros rushed through the city on their daily errands. Dealing with the multitude of limitations gifted to them by Cuba’s Socialist reality, they reminded me of Muscovites from my own distant Socialist past.

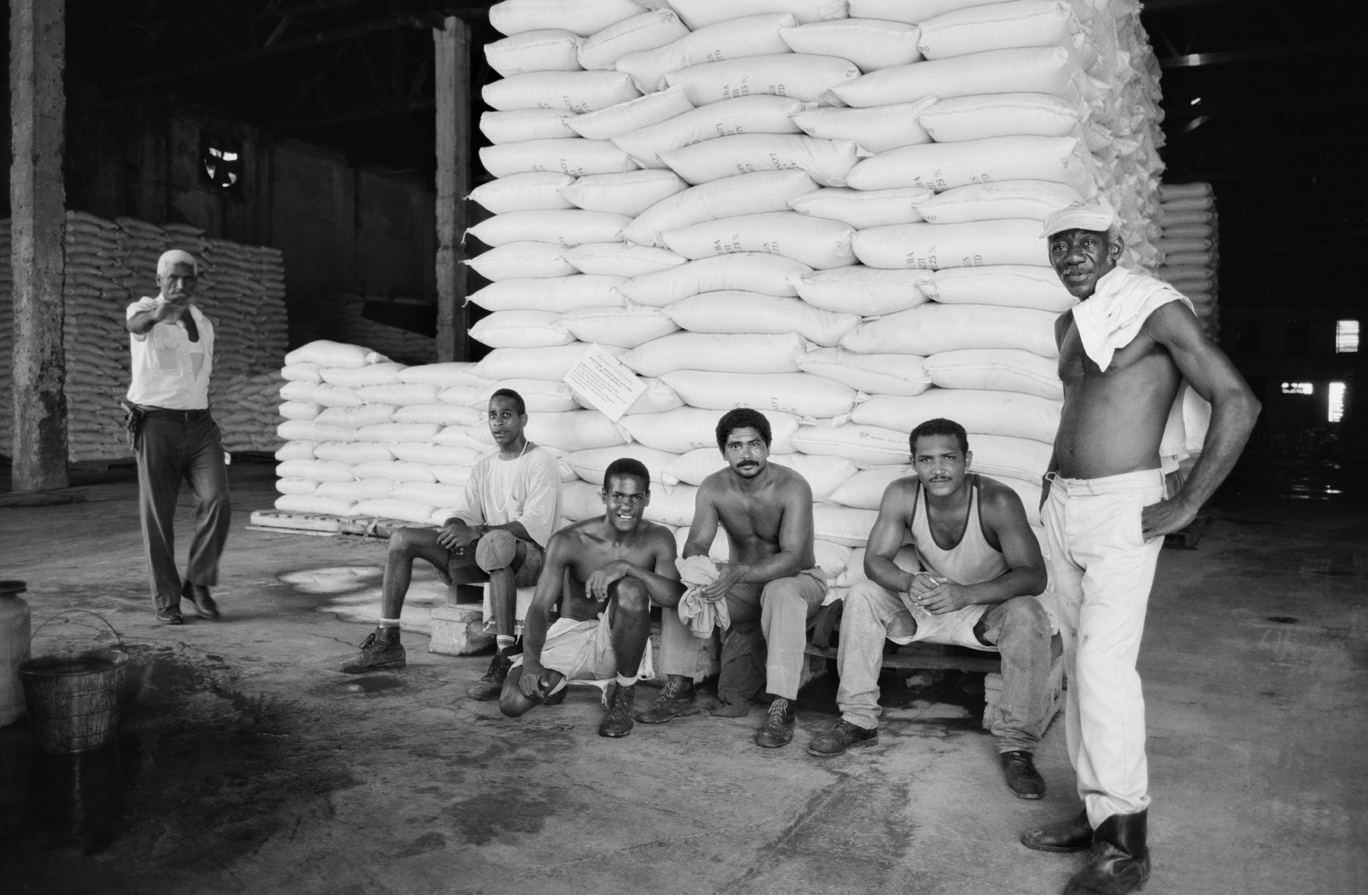

Ilya and I stepped out of our Casa Particular into the blinding heat, looking for a cheap breakfast. We, the lost sons of the former Soviet Union, were determined to discover a state-run restaurant with locals’ only prices. (Most of the eateries in Havana had separate prices for foreigners, up to five times higher than local rates). On our way to downtown, we passed by a butcher shop proudly displaying empty stainless-steel counters, no meat in sight. One butcher slept soundly on the shiny counter; face covered by a straw hat. Another, crouched on the curb in front of the shop, was swinging an axe, bludgeoning with murderous intent a mound of flesh spread out on flattened cardboard box. As we approached, we realized that the flesh was a huge block of frozen fish, imported, probably, from Norway. We were stunned. Wasn’t Cuba an island surrounded by the warm, generous waters of the Caribbean Sea? At least the fish should’ve survived Castro’s disastrous economic policy, I thought. But, no! Cuba’s failing social experiment managed to completely deplete even the island’s once rich marine ecology. As we were to discover three weeks later, while scuba diving near Santiago at the depth of 20 feet, there was no fish in the water at all. Our guide went crazy with excitement when we spotted a lonely lobster crawling through a dying coral reef.

Somewhat disgusted, we tore ourselves away from the maniacal fish butcher and journeyed further into the land of revolutionary consequences. Our intuition quickly led us to our kind of breakfast place, or so we thought. It looked like a classic Soviet style “stolovaya”, though the tables were covered with dingy white cloth and the waiters wore faded coattails. While nearby eateries hustled and bustled serving expensive fast food to the tourists and habaneros alike, this one was practically empty. Its clientele consisted of six or seven, dignified old men, each occupying a separate table, looking like the last pieces on a chessboard. They all observed our entrance with evident scorn – either because we were foreigners, or because we were grown men wearing shorts. The waiter’s doubtful look at our attire made me think it was the latter. His hesitation to serve us was dispelled by a lazy wave of the manager’s hand, whereupon we were seated and given a soiled single sheet of paper with a faded stamp – the Menu.

Never mind the coattails – this was by no means a fancy restaurant. The menu was priced in Cuban pesos and the prices were outrageously low, even by local standards. The short list offered only six items: vegetable soup, two egg dishes, two types of sandwiches and a vegetarian spaghetti dish.

I looked around trying to determine the quality of the food by the customers’ reactions to what they were eating. Most of them seemed to be enjoying the soup a great deal. Following their lead, I ordered the soup and a ham sandwich. My friend ordered huevos rancheros. The waiter brought over a basket of bread. Famished, I bit into a slice and gagged on the rock-dry crust scraping the roof of my mouth. There I sat, unable to swallow, mouth full of bread shards. Luckily my soup had arrived and I greedily slurped down a few spoonfuls, then gulped and pushed away the bowl. It was good only for washing down dry crust; otherwise, it was cold and downright inedible. As I was processing its sour aftertaste, the waiter put in front of us my ham sandwich and Ilya’s huevos rancheros. Suspicious by now, I lifted the top, razor edged crust off my sandwich only to discover a lonely, paper-thin slice of ham. No mayonnaise, no butter, no mustard. My bargain breakfast was over.

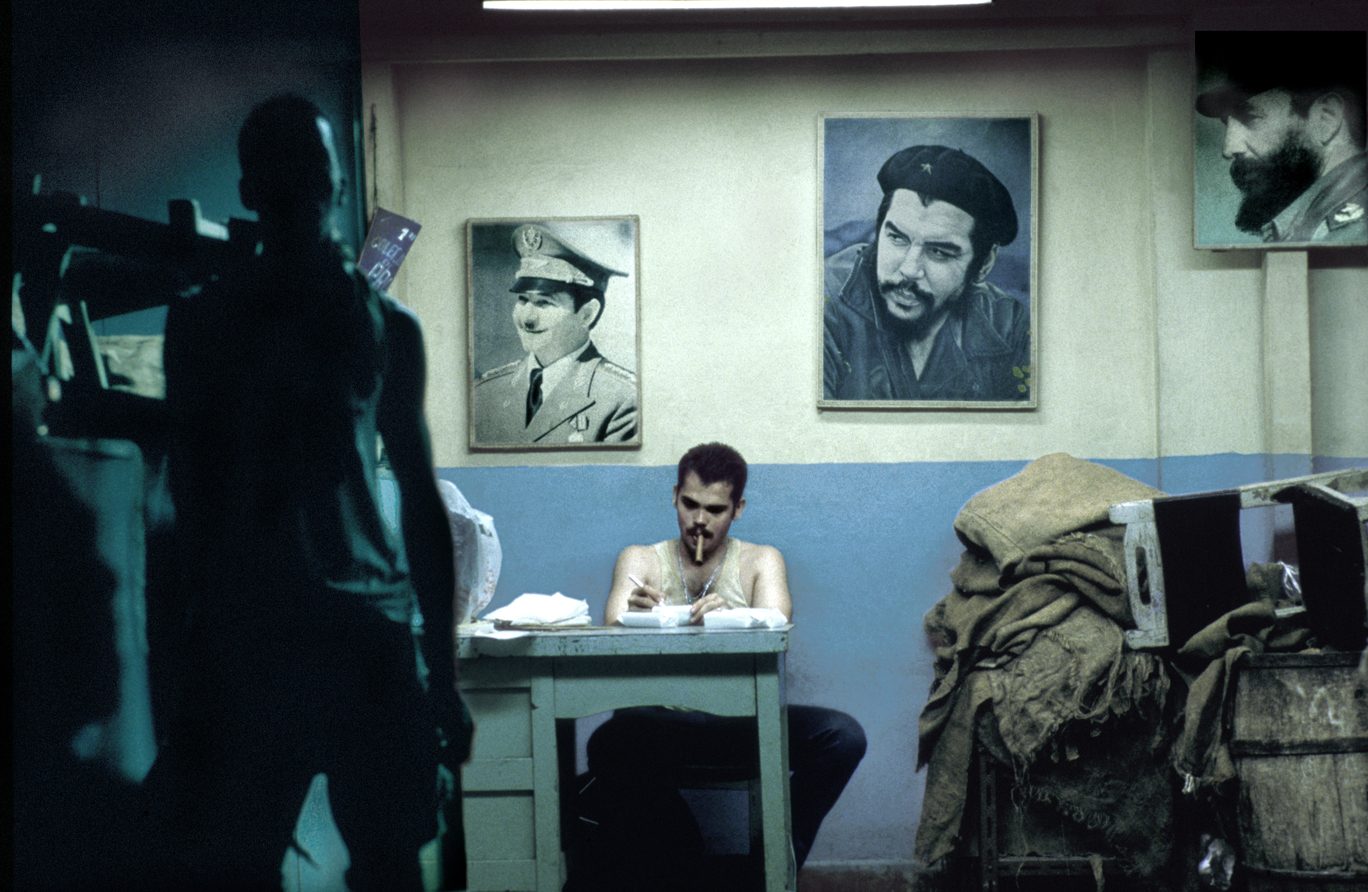

The tang of the soup still on my breath, I once again examined the weathered clientele of the establishment. By now most of them had finished eating and sat facing the street, crumbs clinging to their mustaches and chins. No one spoke or read. Everyone’s gaze was focused on city life running its course beyond the restaurant’s windows. With pained expressions on their faces, they watched the Havana’s daily circus, as it was some other dimension. I looked down at my menu. “House of Veterans Café no. 5”- I made out the fading stamp at the top of the sheet. And then it clicked – the prices, the stale, dry bread, the bleary eyes of the patrons…these were probably some of the heroic men who fought alongside Castro in Sierra Maestra, spilling their blood for Fatherland and Revolution.

Now, retired and penniless, they were getting their daily free meals in this pitiful government–run restaurant. I no longer cared about the quality of food. I felt sad. I also felt a pinch of a fear that, after 20 years of living in the US, I suddenly found myself caught in a timeless re-run of Soviet reality I once knew only too well.

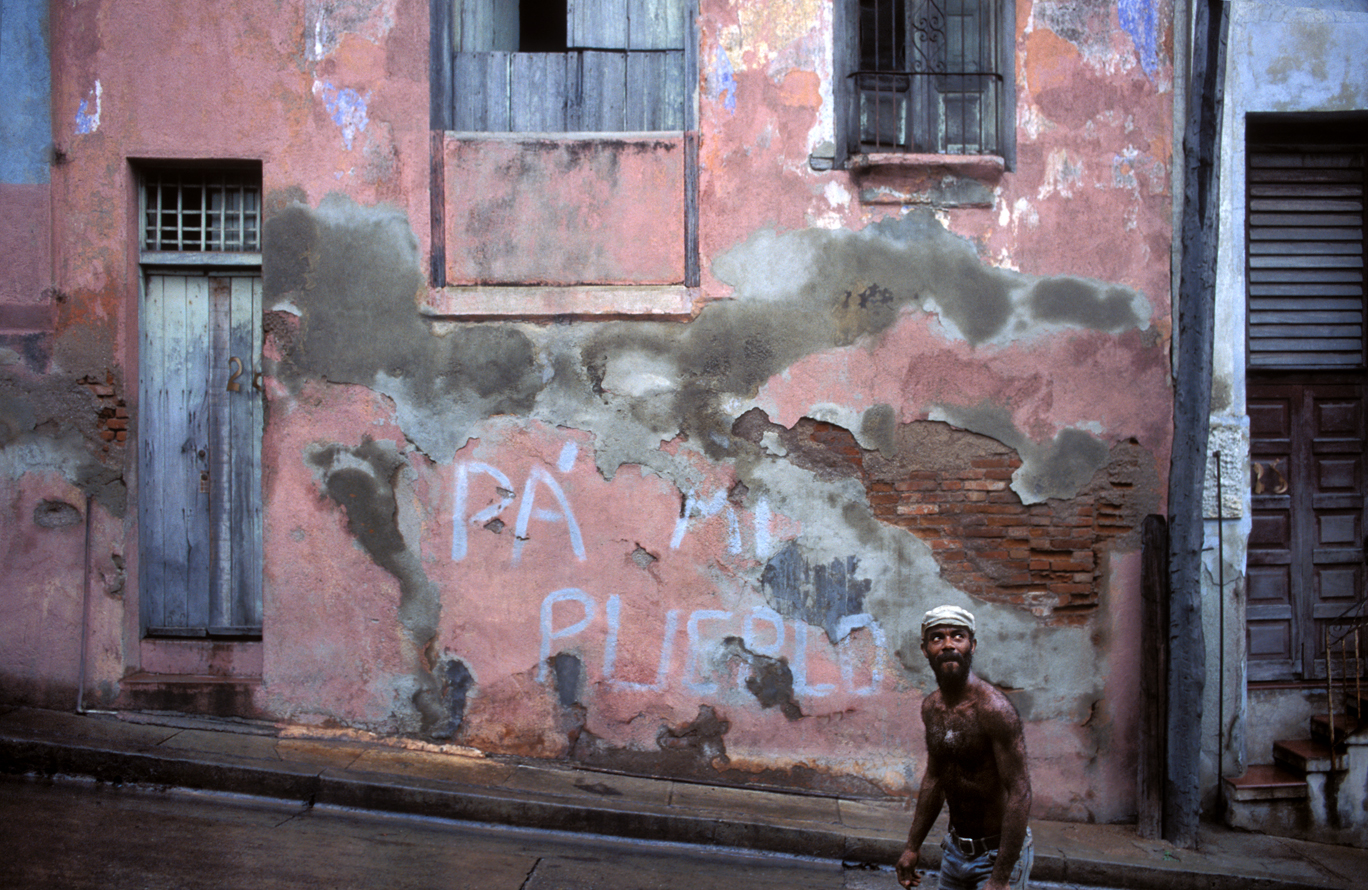

But that feeling had quickly passed. We were back on the colorful, dilapidated streets of Havana. The city was basking in the midday sun, awaiting a tropical downpour. The ice cream was good and cheap, people were smart and friendly and women were beautiful beyond words. Above all, my friend and I were gringos on vacation.

This trip was monumental for us both. We managed to cross the island by car, from Havana to Santiago de Cuba, stopping in every town on the way. We spent a week in Trinidad de Cuba, an old pirate port, and visited Castro’s headquarters in Sierra Maestra. We chased Cuban women, danced salsa, smoked expensive cigars and drank cheap rum. We fell in love with the place and I fell for an island girl.

Since then I returned to the island several times. On my last visit I found Castro and the embargo still firmly in place. I checked in on House of Veterans #5, and found it to be in “full swing”. Not much has changed in Cuba over the last few years. Castro’s utopian policies persisted, as the veterans of revolution slowly passed away. Strangely, this pattern seemed to be as constant as the beauty and intelligence of Cuban people.

© Andrei Rozen